|

A good friend and comrade has been

to visit us in Milan: he is Pietro Vermentini, who has been

living in Chiapas for over three years, working in the field

of popular education through the FOCA organization (Formación

y Capacitación - Training and Education), a Mexican organization

active in both the educational and the health spheres, focusing

its actions on the recovery of traditional indigenous medicine.

Of course, we could not miss out on this opportunity to find

out more about what is happening in Mexico.

Not so long ago, not a day passed without news of what was

happening in Chiapas. Is the fact that we hear less talk of

it today due to a conscious choice by the media, or has the

situation really changed?

I believe there have been events recently, such as the Ocalan

case or the war in Kosovo, that have - obviously - attracted

the attention of both the media and our comrades here, but this

doesn't mean that the situation in Chiapas has 'normalized'.

From what you have been able to observe, in what situations

can you detect the strongest trace of a libertarian attitude?

There are certainly very strong traces in the autonomous municipalities;

we need only think that one of the most important Zapatista

communities is called Flores Magon, named after the Mexican

anarchist who was most representative of the libertarian side

of the Mexican revolution.

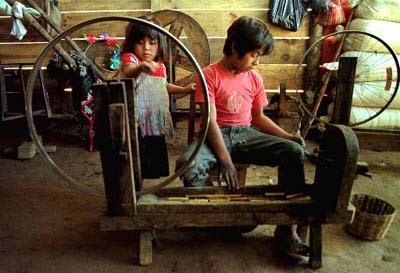

The municipalities are an experience that links up with the

indigenous community tradition. While in other South American

guerrilla wars of a Marxist mould there are orthodox links with

models used at any latitude and with any culture, with forced

collectivization of the land, in the Zapatista case, each community

decides for itself, creating a large variety of situations,

with communities that have decided on completely communal ownership

of the land and others where a mixed system is in force, with

common land and individual land; in some cases a couple that

has married receives a piece of land from the community.

All through direct forms of democracy, without decisions from

above.

There is a substantial difference between the Zapatista army,

which has its own internal rules, and the bases of grass-root

support, which self-organize by means of the community assembly.

Contacts between the communities are maintained by the CCRI

(Clandestine Indigenous Revolutionary Committee), a collective

organization that can only take important decisions after consulting

the communities.

Through the tool of the assembly, communities with Zapatista

majorities but with strong minorities supporting the government

manage to coexist, also because the Zapatistas have never seen

the indigenous Priista [supporter of the governing PRI party]

as an enemy, but more simply as someone who has bowed down in

order to eat.

A tactic widely used by the government to divide indigenous

communities is to guarantee privileges to those who move away

from the Zapatistas - a sack or two of corn or a tractor are

very convincing arguments for those who are struggling to survive.

This campaign of delegitimization had its peak in May last year,

with the psychological offensive of desertion: in all the Mexican

media, great prominence was given to the supposed mass desertion

from the Zapatista ranks, with the interviewing of fifteen or

so ex-Zapatistas, who accused the EZLN of only fighting for

power and said that because of this many like them were leaving.

Filmed by the television channels, they ostentatiously took

off their balaclavas, declaring that they wished to enter lawful

society again, accepting the government proposal: "A machine

gun for a sack of grain".

Of course, two days later the Zapatista army provided the names

of these people and their communities of origin, declaring that

they had never been Zapatistas, and that they had each received

a new tractor for this service: you need only go and see them

at their homes. But this counter-information had no outlet in

the media.

It is also true that one quality of the Zapatista army is that

of allowing to return home those who, after years of guerrilla

in the forest, are tired and prefer to help the movement in

some other way, obviously provided they don't become informers.

This is no minor difference from other guerrilla wars, for which

there is no return ticket.

What role do Mexican anarchists have?

The Mexican anarchist movement is small-scale; nevertheless,

it is seeking to support the Zapatista initiative to the maximum.

In the past the "Love and Rage" collective opened

a libertarian school in Zapatista territory, but the experiment

ended badly, because of the ambiguous attitude of certain individuals.

Currently small groups or individuals operate in Chiapas, and

in Mexico City there is a large group of youngsters who publish

the magazine Letra Negra

What kind of numbers can the Zapatista movement count on

today?

It is difficult to quantify the support the movement enjoys

in the cities and towns, particularly in a reality so multiform

as Mexico.

One indicative figure - though numbers may well be considerably

larger - is that of the voters at the last consultation launched

by the Zapatistas: over three million people voted. This is

not an exceptional number, considering that the country has

ninety million inhabitants, but you must consider that almost

half the population is under fifteen years old, that the news

of the consultation was by word of mouth alone and that only

a million people participated in a similar initiative in 1995.

What type of relationships have the Zapatistas been able

to create with Mexican civil society?

Despite the continuing desire to forge alliances involving

other sectors of Mexican society, it is hard to make any headway.

Yet something is moving; the university was occupied recently,

something that hadn't happened since the harsh repression of

'68. The protest started in Mexico City and spread to the other

universities in the country. The reason that sparked the protest

was the shocking increase in university fees, but very soon

the matter began to take on political implications. A delegation

from the EZLN went to establish contacts with the students.

The government is in difficulty in this protest, because they

cannot identify the leaders, to buy or frighten them off, as

- at the moment - the movement is based on an assembly model

and those negotiating are only spokespersons on behalf of the

assembly.

This method was borrowed from the Zapatistas, who don't take

any important decision without first consulting the communities

supporting them. This is the great challenge for the Zapatistas:

not to win a war militarily (one already lost at the start)

but to involve the people, to decide their own destiny.

This challenge meets with powerful resistance from Mexican civil

society, dominated by logics of power, by micro-factions, so

grass roots organizations struggle to take off.

The Zapatista Front (an organization created precisely to coordinate

civil initiatives) continually seeks to stimulate the birth

of new autonomous focuses and indeed that was the purpose of

the latest consultation: to encourage self-organization. In

fact, to administer this vote two thousand civil brigades were

formed throughout the country. These did not dissolve after

the consultation; quite the opposite, they created a national

coordinated structure.

The Zapatistas refuse to direct movements from above; their

proposal is very simple: "we will not structure you, organize

yourselves". Unfortunately Mexican civil society is not

used to this libertarian approach, and many can't manage to

free themselves from authoritarian mechanisms, those of delegation.

At some meetings of the Zapatista Front, when faced with important

decisions, some delegates ask to adjourn the meeting to report

back to the community, while others - with the excuse that it

is necessary to act quickly - go beyond the delegate powers

they have received. Unfortunately civil society finds it difficult

to accept direct forms of democracy. This type of resistance

is less noticeable in Chiapas, in the indigenous communities

that traditionally adopt these methods.

And perhaps the peculiarity of the Zapatista movement is their

knowledge of how to interact with this basic cultural identity.

The difficulties are our own: a lot of Mexican and foreign organizations

that use the Zapatista message as a reference point in reality

have an internal structure that is hierarchical and authoritarian.

But the Zapatistas do not give up; they know that much time

is needed for change to take place: they direct their message

at society, not at power, and therefore the time needed for

the transformation is long, but the important thing is to proceed

along the right path. The EZLN discourse is this: "we don't

want power for ourselves, because nothing guarantees that we

will not end up like our oppressors. On the contrary, we want

to decentralize it, to dilute it, so there is less power and

more participation".

Currently, what is the effect of the presence of the government

army?

Considerable; among the guerrilleros operating in the Lacandona

Forest and the support communities, the possibilities for exchange

have been weakened: the strategy of the army is to deprive the

Zapatistas of their social hinterland. This initiative has borne

fruit for the army, because now it is much more difficult for

the Zapatistas to participate in the life of the community.

Yet these community experiences are hard to liquidate, as they

are so deep-rooted; they have brought about substantial changes

not only to land management plans but also at a cultural level.

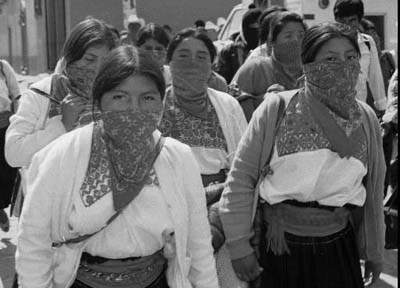

We need only consider the role acquired by women in community

decision-making; for instance, in the Zapatista communities

it is forbidden to drink alcohol, on account of the clearly

devastating effects this produces on indigenous people, and

this decision was made at the insistence of the women. Let's

not forget that women represent one third of the Zapatista forces,

the highest presence among Latin American guerrillas. As Comandante

Ana Maria recalls: "In the EZLN relationships between men

and women are on a level of perfect parity". This is no

small matter, considering the ultra-macho attitudes existing

in Mexico.

But don't you think there is a contradiction here, with

Marcos' role within this experience, as a charismatic leader?

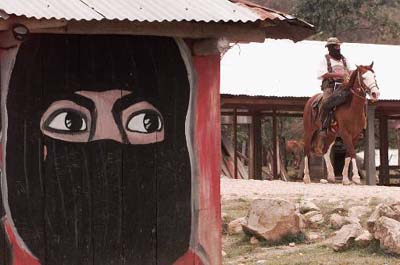

The danger of transforming Marcos into a sort of icon does

exist, but he is the first to be aware of this, and does not

waste a single opportunity to ironize about it. After all, the

Marcos myth is more a construction that is external to the Zapatistas,

where in reality a very much more collective decision-making

process exists than people would think: the Command of the EZLN

is not Marcos, but a collective body, it's as simple as that;

the fact that Subcomandante Marcos is an excellent communicator

and an effective symbol for the Zapatista struggle is a whole

other story.

Interview by Dino Taddei

Interview by Dino Taddei

(English translation by Leslie Ray)

*For those interested in contacting

the editors of Letra Negra, the address is:

inegra@hotmail.com

or

C.P. 8935 Admon. Palacio Postal, 1

06002 Mexico, D.F. |

|