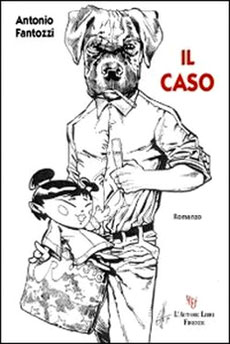

|  A cop A cop

too different

National smoke only. Can you imagine the patient as Job, but has occasionally bursts of violence. Badly dressed. Often runs in slippers. "The police officer in a bizarre Italian comedy" so you think. He has a face like a bulldog, but some would say that looks a bit Alberto Lupo or Amedeo Nazzari. When he talks sputtered. "They're made more for the brothel that for the church even if I attend neither the one nor the other." Commissioner Ernesto Donadei is not liked by his superiors and is a troublemaker. Wanders when he speaks. He loves the cinema and difficult words. He believes in justice. For this reason only he is interested in those rags and "broken bones" that were once a Chinese girl.

Against the background of Reggio Emilia worsened and silenced, on the hunt for a serial killer who enjoys torturing, Donadei is one of the policemen ("cops" he would say) the most unusual we've seen in Italy. It is better written. Yet Il caso (256 pages for 16 euros) by Antonio Fantozzi is published by a small publishing house (L'autore Libri Firenze). Struggle to find ... but worth it.

Little can reveal the plot - like any self-respecting detective story - but the reader feels an advantage over Donadei because from the early pages, he knows that the serial killer and there is a girl. But if it were not so?

The 'red' chapters are the thoughts of a child who grows up with the desire to kill and torture, those 'black' accompanying research Ernesto Donadei. Every so often, the colors blend, or to list a mysterious Antonio with short stories.

Few news about the author and lives in Regggio and has already published a collection of short stories (mixed with travel notes) on Senegal. His writing is chameleon: oscillates between an almost unbearable cruelty and clarity of "scientific" if it digs into the head of the (alleged?) Murder while tangled in wisdom, crazy when he deals with thoughts and actions of the commissioner. Play with images and metaphors and more effective out of the ordinary: the red swamp crayfish, the Magician, pornography, trees, the story of Billie Holiday and Abel Meeropol.

Everything is "circulating" as the endless roundabouts of a city that turns out to be as Reggio. So many beginnings and many end users. The first half page Donadei insinuates that's crazy or convenient to believe that all face. We repeat the protagonist and the author (with the firm "Matrix") that "ignorance is good." Perhaps this is precisely the point. As for Reggio who do not want to know what has become of their city, "loneliness and wickedness," Cement and fireflies, cooperatives and the Camorra. Unforgiving thoughts or stories Donadei Antonio. "Did you ever think? At the hearth of the Philippines, elderly carers slave, pampering African whores ... Here is the globalization of feelings explained to the children. "

Striking down Fantozzi. It is perhaps also why I find it hard to find publishers and reviewers. But who will read this survey will not forget this cop ... not too different to be crazy.

Daniele Barbieri Daniele Barbieri

These exceptional

“Free women”

She appeared in late December of 2010, the precious (Eulàlia Vega, Pioneras y revolucionarias. Mujeres libertarias durante la República, la Guerra Civil y el Franquismo, Barcelona, Icaria, 2010, pagg. 389) collection of testimonies of libertarian militants in Spain before, during and after the Civil War (1936-39), combining history and women's oral history. Sources methodologically valued differently by the researchers on contemporary Spain, which have borne fruit in the past. The first side - the history of women in conflict - remember the studies of Mary and Martha Nash Ackelsberg, and more generally on the war, but focused almost exclusively on the enormous potential of oral testimony, the pioneering work across the board by Ronald Fraser and the more detailed and limited to Albalate de Cinca (Huesca), the Netherlands Hanneke Willemse1.

The work of Eulalia Vega, a researcher and lecturer at the University of Lleida, after some general remarks on the value and use of oral sources, immediately goes on the merits, with ten stories, organized around five times.

It starts with the youth team of the protagonists, including family life and neighborhood.

The militancy before the outbreak of the conflict, in particular during the Second Republic (1931-1936), is the second time. The fundamental questions to which you are trying to find an answer is not trivial: why and how they began their participation in the multiple joints of movement? In the trade union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) as part of Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and the Youth libertarian, libertarians in universities and schools rationalist, and more generally in various forms of socialization promoted by Spanish anarchists. What positions occupied the women? They were truly marginalized by men, as is often claimed?

The key moment is obviously represented by the hot summer of 1936: first in the streets to foil the Franco coup, then to the front as militants, but especially in communities in the rear to make up for the volunteers left for the war.

It is during this time that in addition to moderate Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas Guidance Communist-led by Dolores Ibarruri, there is a new anarchist association Mujeres Libres, clearly linking the issue of emancipation from capitalist exploitation to the patriarchal oppression. Only a minority of women, however, there are sharpened, about 20,000. Why? What new roles assumed during the militant libertarian revolution, perhaps the most radical of contemporary Europe? In areas such as their claims were able to translate into practice? Are more important questions addressed by the research of E. Vega.

The fourth section explores the moment of military defeat, the desperate flight to the Catalan exile border in January / February 1939, the bombing enemies, the heavy conditions that the refugees lived in hiding in France during the Second World War threatened to be delivered by the occupying German police to Franco.

Only since 1945 our refugees generally obtained recognition of their rights, and this time there is the choice between a possible clandestine return to Spain to resume the struggle for freedom that tarry still plenty to come, or rebuild a "normal" life in their adopted home, waiting for (but never passive!) the end of the dictatorship of Franco (1975).

The beautiful stories of our witnesses, mostly nineties at the time of recordings (some of them we have since left), recompose a dense fresco, continually moving from private to public, from individual to collective life, with vivid brush strokes that leave a deep emotion and admiration in the reader.

Renato Simoni Renato Simoni

- M. A. ACKELSBERG, Mujeres Libres. El anarquismo y la lucha por la emancipación de las mujeres, Barcelona, Virus, 1999 (traduzione italiana: edizioni Zero in condotta, Milano 2005). M. NASH, Rojas. Las mujeres republicanas en la Guerra Civil, Taurus, Madrid, 1999. R. FRASER, Recuérdalo tú y recuérdalo a otros, Barcelona, Critica, 1979, 2 voll.; H. WILLEMSE, Pasado compartido. Memorias de anarcosindicalistas de Albalate de Cinca, 1928-1938, Zaragoza, PUZ, 200

De André De André

among the benches

The back cover is categorical: "Fabrizio De Andrè is even today, for years after his death, one of the few people able to speak to young people." Very true, apart from a vague category of "young".

Hence the idea of Maximilian Lepratti: organize logical threads and materials to offer "De Andrè in class', the book is published by EMI (128 pages, 9 euros) with a preface by Don Andrea Gallo.

The first half rebuilt, good ability to synthesize, "as his songs were born": the years "French" themed albums, the term "American", the retreat in Sardinia. works "ethnic." Faber Lepratti then shows how it can be used in schools in at least four different contexts: history, music, "between philosophy and intercultural" and of course in literature (French and Italian but also English). Wanting to deepen the musical instead will find many links-De Andrè debts with schools or traditions, which are arranged at least 6 boxes: the late-medieval, the English folk song, folk dancing, the styles of Latin America, some American folk, classical music .

There is no doubt that, in theory, those who teach - in school or who are organized and sold spaces - can be found in his songs excellent ideas for classroom work. But in practice it is possible that at the time of skuola (back increasingly authoritarian) and squola (recommended from ignorance), where hardly any areas of resist free thought? There are those who try, convinced - as suggested by Don Gallo - which Faber aid because he has always traveled, consistently, on two tracks: 'anxiety about social justice and hope for a new world. "

I can tell you that months ago and entered the high school of Ravenna Dante Alighieri in self-management among the 36 (!) Laboratories in one morning, stood under a beautiful "De Andrè and apocryphal gospels." Hurrah. But the hypocritical and the school culture (the many who now pretend to cheer after Faber censored in life) is capable of anything. As I write this review that I read in middle school, "Fabrizio De Andre ', Rome (quatiere Monteverde) the" voluntary "contributions of families become mandatory and therefore no field trips or other extracurricular activities for those who do not pay. "What we have is not your bank account" is not it?

Daniele Barbieri Daniele Barbieri

|

A writing on the walls of Rome

(photo Chiara Lalli) |

The myth of The myth of

natural society

In the history of Italian anarchism, the figure of Pietro Gori occupies a significant place: it was actually, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, by far the most popular exponent of the movement. Recently, it was held in Pisa a conference on his political, social and cultural at the same time the Library Serrantini published by Maurizio Antonioli and Franco Bertolucci, an anthology of his writings: Pietro Gori, La miseria e i delitti, BFS, Pisa 20011, euro 14,00; anthology that includes topics related to sociology and the sociology of criminal prosecution: one set of problems that had to be part of the "poet of anarchy" primary attention. The introduction of Antonioli and Bertolucci, however, also gives an account of the broader relationship between Gori and the history of the labor and socialist movement, addressing some important ideological and historiographical issues.

From a strictly scientific, poverty and crime can not be considered a text of relevance today. Its importance lies rather in representing a clear example of the progressive era mentality, which, in turn, reflects, in this case, a common political faith and not ideal because it highlights the profound sense that animated a part of anarchist intellectuals and so, consequently, shows the weight and significance of his militancy and propaganda of the impact it has had in the lower classes.

The most important figure in the intertwining of the interpretation is the deterministic Goriane belief, then dominant, with the volunteer ethic. It is therefore read The misery and crimes in the light of this whole problem. Summarizing the most we can say that does not come from Gori culture of his time, that is, from positivism. His view reflects an almost decisive of this vision, which gives the science achievement of truth, be it social, political, economic or philosophical. In his view the story is the trustee of a path for continuous improvement of the human race. The vision is based on a substantial Goriane anthropological optimism, with an enlightened approach emphatically, that all the past is judged in a negative way.

In Gori positivism there is continuity between the physical world and the moral world, since only those determinations of the different expressions of the same reality. In fact, the same laws that control the fate of the natural world also govern those of the moral world. It follows that the action of men is organically incorporated seamlessly into all this, it is essentially free of personal independence. And with that Gori resumed the polemic against the materialistic conception of "idealistic" free will, which means regardless of the binding nature of the historical, geographical, economic and social development. The human will, despite the illusion of being free and sovereign in its choice, it is only subject to external forces and internal, physical, social or moral in their mix, so the choice of the will is ultimately the pressure unnoticed, but not least the existing grounds of mental joint agents on the desire itself. And as you can not escape the physical and natural environment, so you can not escape the socio-historical context. Hence the obvious predominance of society than the individual, which is, in a sense, influenced decisively by the environment around.

Post all of these premises, then it is legitimate to ask: what motivates human beings to the rebellion and the quest for freedom? If you are physically and socially determined, as able to become free? Gori replies to these obvious questions, referring to Kant and Guyau, states that if the man is the son of the environment is "of himself," that his moral sense, which requires them to recognize the rights of others pushing to respect it. Hence the idea that the revolutionary sense is a moral sentiment, so the rebellion is nothing but a right of legitimate self-defense requires that the violence in the individual and society, it is the moral foundation of the revolution against any form of tyranny, even though "the moral anarchy and the complete negation of violence."

Since man is one with the society, this should be able to meet the needs of irrepressible individuals. Only a society free from oppression of private property may be able to cope with this task. Therefore, the anarchist society can only be that the social system where the solution to the problem of freedom will assume ownership of a socialist solution, solution, in turn, that will reach its full application only through the principle of common justice ("everyone gives according to its forces and receives according to his needs "). In fact, anarchy is not the necessary and inevitable culmination of socialism because socialism if it means the end of all exploitation of man by man, anarchy will mean the abolition of all authority of man by man. That's because, rather than proclaim abstract rights, it is much better to talk about specific needs, which is the substratum of every positive law. Conceived in their ultimate essence (i.e. in their natural reason), they are reduced to a right to live and the right to love. On the other hand, the fulfillment of these primary instances can occur through natural character completely spontaneous and free in their operation, which implies the need to follow the flow because it coincides with the intrinsic character of "nature" of society.

It emerges through determinism of positivism, a classic topos of anarchism, that the myth of the natural society which exists prior to "degenerate", following the historical development: in short, anarchy is the natural culmination of the society culture. We are, as you can see, the clichés of Rousseau, Godwin and Kropotkin. Gori, in fact, emphatically asks: "admirable order of nature he has need of other laws, except for those rigid and inviolable from which depends the whole existence of things, and the development of the facts and phenomena? No! Because this is the true order, and its laws are obeyed everywhere without the need for the police, because if someone goes against them in his disobedience is the deserved punishment. "

In conclusion, anarchy is finally discovering the true social order, so as to conclude that "today's revolutionaries are the real elements of order."

Of course, the realization of this utopia will not lead to the creation of the perfect society, the achievement of universal happiness, because evil "will not disappear altogether; it though," greatly decrease the amount of human suffering.

Nico Berti Nico Berti

|